Like any plant, trees grow according to the fertility of the soil and the type of climate in which they grow. For example, a pine tree does not develop in the same way in the mountains as it does on the beach. Of course, there are varieties of the same genus that adapt differently to each place. Today we are going to talk about three varieties of the Quercus genus - Quercus Robur, Quercus Sessiliflora (or Quercus Petraea) and Quercus Alba or simply, Oak, because this tree has an important and ancient relationship with wine.

In the Roman Empire, containers made of oak to store wine were used not only because it was an abundant resource, but also because its a hard wood, but despite its hardness, they could also heat it and shape it into a barrel without the need for glue to join the staves. In addition to all this, oak, they discovered, gave a favorable flavor to wine and gave more complexity as it interacted with small amounts of air that enter the barrel. But not all oaks are created equal and there are many aspects to consider in the process of using it.

I want to talk a little about the taste of oak and how it affects wine. First, it is essential to know that the most common types of oak for making barrels are French and American. French has two types: Quercus Robur and Quercus Petrea. The American version is Quercus Alba. It is important to mention that both types of French oak can be found in many areas of Europe (even Greece and Iran), but for wine barrels the best ones are those that grow in cooler forests. We will talk about this later.

No oak is better than another, but it is always preferable that the flavor that each one imparts is integrated with the type of wine. If not, the flavor of the wood will dominate. We already know that over time if there is no balance, the wine does not improve. While we all have our own tastes, I believe that nobody wants a wine that tastes like sawdust, so it is important to do the necessary tests and studies before putting the entire production in barrels that are not the right ones for each type of grape.

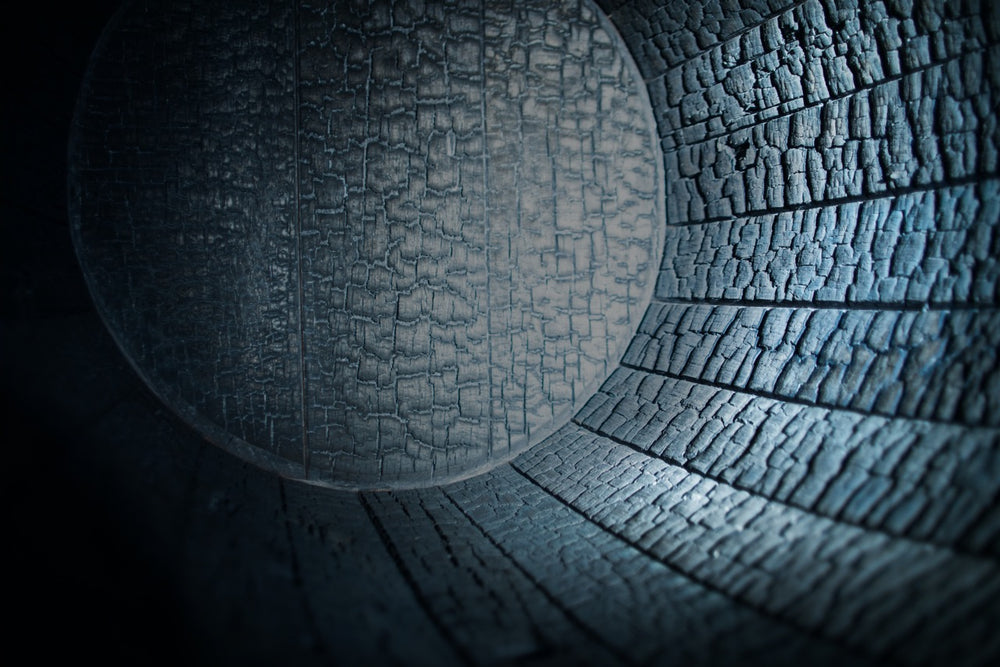

How do we know if it's the right type of barrel? Many wineries make small batches to experiment, but there are also parameters we can follow. Remember your biology classes? Each ring in a tree is a year. Within these rings there are ways to tell if it was a rainy or dry year depending on how big the holes of the xylem are, also called “spring wood.” In cooler and drier areas, the rings (and therefore, the spring wood) are tighter than in areas with more rain and heat. Along the width of these rings we find the grain, and the tight grain of cooler areas gives oak flavors in a gentler and more gradual way. As such, we know that the cooler forests of France such as Troncias, Vosges, Nevers and the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa in the USA, produce the most desirable oak for wine. However, they are not the only options. It is the decision of each producer and some prefer American Oak that has stronger flavors. However, a delicate grape like Pinot Noir or a barrel-fermented Chardonnay are not normally stored in American Oak.

The way oak is seasoned matters. In France and other parts of Europe, the common practice is to expose the already cut trees to sun, wind, snow and rain for two to four years to remove the strongest tannins from their wood. In the US, drying in a kiln is more common. With the American system, plus its early wood with the thicker xylem holes, it's easy to surmise that the flavor is more tannic and strong. This may be desirable for some wines and not for others. It is part of the winemaker's decision and depends on the wine they are making. Also, the cooper toasts the barrel in the manner which the winemaker asks for: light, medium, or dark. The darker the toast, the more oak, coffee, chocolate flavors.

The way oak is seasoned matters. In France and other parts of Europe, the common practice is to expose the already cut trees to sun, wind, snow and rain for two to four years to remove the strongest tannins from their wood. In the US, drying in a kiln is more common. With the American system, plus its early wood with the thicker xylem holes, it's easy to surmise that the flavor is more tannic and strong. This may be desirable for some wines and not for others. It is part of the winemaker's decision and depends on the wine they are making. Also, the cooper toasts the barrel in the manner which the winemaker asks for: light, medium, or dark. The darker the toast, the more oak, coffee, chocolate flavors.

The age of the barrel is also important. A new barrel will impart stronger flavors that will be reduced each time it's used. It takes up to four or five uses to become neutral. Still, barrels can be used for dozens of years. Most producers use a mix of new and old oak, some only use old and some only new. But the most common is a mix of new and used. At between $1,200 and $4000 USD per barrel, it makes sense to use it as long as possible. However, too much new oak does not equal a better wine. Too much oak can ruin a wine just as much as too much salt ruins your dinner. When the winemaker finds the best type of oak for his wine, knowing at what point to draw it out and in what percentage to use old or new oak is their art.

Another important characteristic is size. The smaller the barrel, the more oak flavor it will have. This is a simple concept; there is less wine in a small barrel, so there is more contact with the staves. The different sizes of barrels are: Bordeaux barrels are 225 Lt. Burgundy barrels, also called “ pieces,” are 228 Lt. For those looking for less oak flavor in their wine, there are puncheons (500 Lt.) or demi-muids (600 Lt.). And the even larger ones foudres (30,000 Lt.), look more like tanks than barrels and are used for wines that the winemaker decides have less oak flavor.

The last thing that happens during the oak aging stage, and perhaps the most important, is the slow exposure to oxygen. Think of what happens to the wine poured into the glass or bottle during the time we are drinking it, for example; it is the same process that happens in the barrel or over time in the cellar, but it happens much faster in the glass. The tannins that come from the grapes and the wood of the barrel begin to soften when they come into contact with the air. With evaporation in the barrel this also happens. An oak barrel can lose up to 20 liters or more of liquid during a year, so it is extremely important that it does not have too much exposure to air, to avoid oxidation. To mitigate this, the winemaker fills the barrel with a little wine several times a month—depending on how dry/hot or cold his cellar is. “The Angel's Share” is my favorite term in winemaking coined for this process. It's the name given to the evaporation effect of the liquid in barrel. Angels or not, it is very important to ensure that it does not evaporate too much to avoid oxidation and volatilization, which threatens the wine's stability. In addition to “The Angel's Share”, a little air always enters through the mouth of the barrel. This infusion of air is what breaks the molecular structure of the tannin, leaving them softer and opening up the molecules of aromas and flavors during aging. Finally, during barrel aging, the winemaker racks the wine to separate it from the sediment and clean the barrel. With these movements, the wine also interacts with the air, exposing it to oxygen, giving it more complexity.

I also want to mention that there are other types of tanks that can be used for its aging and that give it other types of qualities such as amphora, cement eggs among others, and the wines that age in them can demonstrate a wonderful purity. Even so, Oak is still number one in the world. Wine and Oak have been an inseparable couple for more than 2,000 years, and although the style of making wines with a lot of wood has changed in the marketplace (making wines with more elegance), everything seems to indicate that it will be an eternal bond.

There are wonderful wines that have no oak at all, and they may even be preferable depending on what you are eating, the climate or your personal taste. The important thing is that the winemaker – who has all the decisions in his hands – does the right thing so that you can find the type of wine he produces and that you like. Remember that different types of oak are as varied as different tastes. Search, taste, drink, explore and enjoy the adventure of the wine trail.